"During their usual strolls along the main streets of their home towns, our parents and grandparents gazed at the scenery around them and took for granted a spectacular picture that seldom is observed nowadays and that few of us can hope to see during our lifetimes:

The interweaving limbs of the stately trees that lined the streets ascended into a towering canopy with a graceful, arching beauty unmatched by any tree that is commonly seen today, spreading horizontally at heights often greatly exceeding 100 feet (in rare cases attaining 140 feet with even greater spreads and 11 foot trunk diameters), and drooping long, slender branches in abundance high above the street, blocking all view of the sky. Along countless streets for many miles in cities and towns throughout the tree's extensive native range in the eastern half of North America, even as late as the early 1960's, this scene abounded, the effect of the only species capable of giving us such majestic splendor."

- Bruce Carley, "Saving the American Elm"

The story of the American elm, of the devastation caused by Dutch elm disease, and its aftermath is not just interesting in its own right, but holds powerful parallels for the devastation caused by our neo-liberal economy today. This was brought to mind when progressive economist Prof. Mark Thoma has confessed in a blog entry about The Deregulation Ideology among Economists:

I think Greenspan is getting a bad rap when he is criticized for being anti-regulation with respect to financial markets. Most of us were. Well, maybe I should speak for myself - I was. When you looked at the data and saw, for example, except for the S&L crisis, no or very few bank failures you wondered if there was enough competitive pressure in the industry. In a few years there were literally no bank failures in all of the U.S. At the time, it seemed like regulations such as those that prevented banks from paying interest on deposits above a set amount inhibited flexibility and helped contribute to disintermediation problems, and there were other regulations that also seemed to do more harm than good. If someone had asked me at the time if I thought we needed more or less regulation in financial markets I would have said less.... But there was a general belief among economists that modern financial markets could handle more competition, and a movement toward deregulation.

(my bolding)

That regulatory oversight seemed to produce no visible good and was mainly wasteful, was powerfully reminiscent of an episode in the story of Dutch elm disease.

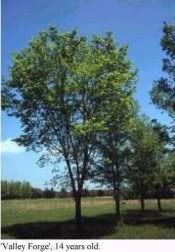

While most of you have probably heard of Dutch Elm Disease, probably few of you have a memory, as I fortunately do, of actually walking down a street like the one pictured above. 100 years ago there were over 50 million American elms lining the streets of most American cities and towns. It wasn't sentiment that led to the planting of so many American elms: if you were to pick a single shade tree to plant on urban streets, the American elm was it -- fast growing (up to 3 feet a year), tolerant of drought, flood, salt, and abuse in general, and a vase shaped canopy that wasn't just beautiful, it was functional (the limbs gradually spead out above building height).

[R]ecalls Hubert Guest, a retired city manager who grew up in the small town of Coffeyville, Kansas: "You could look down the street in the summertime, and you had these great elms that just kind of formed a tunnel of shade."... "You could go eight or nine blocks and these big elms made you feel like you were inside when you were walking down the street."

Unfortunately, the plainting of elms almost exclusively along millions of American residential streets meant that when Dutch elm disease struck, it was a public disaster, just as the serially inflated economic bubbles that "the internet/growth stocks/gold/real estate will make you rich!!!" have led to a credit disaster not seen since the Great Depression.

During or shortly after World War 1 some diseased elm wood was imported from europe, and in the 1920s people started noticing that American elms were dying in what seemed like a plague. With the Great Depression, municipalities had little money to spare, so dead elm trees harbored the insects that infected living trees nearby, and like the great black plague, the vast majority of those elms lining the streets died. As Crowley explains:

The cause of this pervasive syndrome of wilt and dieback was a parasitic fungus....

A native of Asia, .... The parasite was no stranger in Europe, where it similarly had appeared earlier in the century and where its pervasive devastation of a number of European elm species, including the esteemed Dutch elm hybrids which had lined many streets, had given rise to its now-familiar name, “Dutch elm disease.”

Except that a few cities (Washington DC is still one) engaged in aggressive sanitation projects. As soon as a tree was known to be dying of dutch elm disease, it was immediately removed. Result: with no dead elm wood in which to spawn, few insects were propagated, and the infection rate in living trees was slowed dramatically.

Sanitation alone will not stop the spread of the disease, but it will tend to stabilize its spread and prevent epidemic outbreaks. The true value of a good sanitation program is that it allows time for a replacement program so that a community doesn't lose all of its trees at once. Replanting new trees of other species can then proceed on a gradual basis.

The value of a good sanitation program is often underestimated because some people believe that, "The elms will die anyway." Although this may be true, the rate of dying can be dramatically affected. The experience in Illinois is an example. When DED was first found in 1950, certain communities established excellent sanitation programs. Some communities that maintained these programs still had 75 percent of their elms 25 years later. In contrast, communities with no sanitation programs had lost all of their elms.

- North Dakota State University, "Dutch Elm Disease"

But after a few years, in many towns, when local politicians were looking for budgets to cut, the elm sanitation program was among the easiest to end. After all, it wasn't like many trees were being infected. The remaining elms seemed just fine. And so the sanitation programs stopped.

And sure enough, with the sanitation programs ended, dutch elm disease shortly returned and ravaged the remaining elms.

You see, the result of sanitation wasn't visible. Sanitation didn't lead to any visible change. Rather, the trees looked the same, year after year. Sanitation stabilized the situation rather than changing it. Because you couldn't "see" the result of sanitation (because it made no "difference"), it was undervalued. The price was the ravaging of the population of trees when the stabilization ended, and the cost became visible.

Like elm sanitation, economic regulation seems inefficient. Sanitation is undervalued because you can't "see" the result. You pay for bureaucrats and programs and enforcement and what do you get? You can't see any progress year after year, it seems such a waste. And for a few years after you do away with the regulation, everything still seems fine. It is only when the disease of human greed and stupidity returns to ravage the economy that you see the price. And you see the reason for the regulation in the first place, only after the damage has been done.

But it wouldn't be fair to end this story without hope. The story of the American elm is also one of natural selection at work. The average American elm growing out in the woods is now considerably more resistant to Dutch elm disease than was the average elm of 75 years ago.

It is also a story of how public intervention can bestow a public benefit. After decades of testing, the US National Arboretum within the last decade released 2 American elm culivars, called 'Valley Forge' and 'New Harmony', that are highly resistant to Dutch elm disease. (In addition to Crowley himself, he footnotes several dozen nurseries selling these cultivars on a wholesale or retail basis).

If the American elm is slowly making a comeback,

so can we relearn the lesson that the enforcement of economic vigilance and sanitation are necessary to a healthy economy and a healthy society.

Comments

what you do not see

Excellent analogy. So many programs, government public service have been cut and I believe one is finally starting to show, the deterioration of US roads and bridges.

Like the airlines, we now have unsafe planes and bankruptcy.

What I find amazing is how no reports on how the industry offshore outsourced plane maintenance about 4 years ago.

When unions tried to fight back they received scant attention.

Airlines were also deregulated in 1978. So Americans want their cheap fares and here we are with a world economy built on airline transport and seemingly the safety of it hitting the skids.