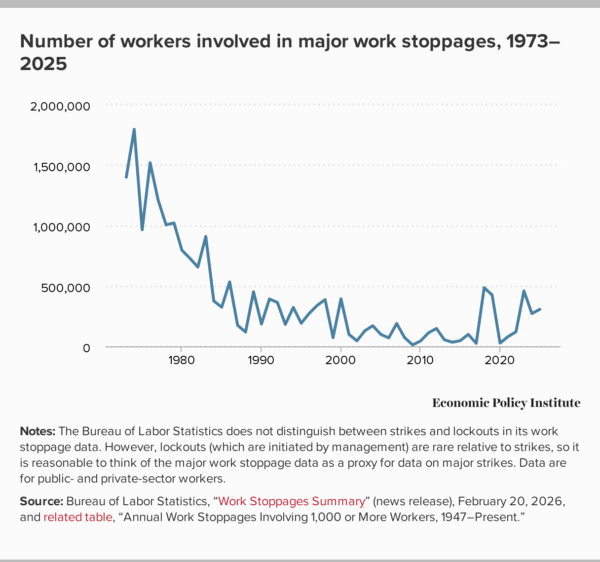

A growing number of workers went on strike in 2025

From sanitation workers in Philadelphia to Boeing machinists in Missouri to nurses in California, thousands of workers across the country went on strike last year to demand higher pay, better benefits, and safer working conditions. New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) show that 306,800 workers were involved in 30 major work stoppages in 2025, a 13% increase from 2024. This is likely an undercount of strike activity given data limitations. However, the number of workers involved in major strikes remains elevated compared with the strike activity that occurred in the early 2000s (see Figure A).

Figure A

Most major work stoppages in 2025 (17) took place in the public sector. Six involved workers at public colleges and universities, including a five-day strike involving 1,400 custodial, maintenance, and services workers at the University of Minnesota where the Teamsters secured higher wage increases and other concessions. Public administration had five major work stoppages and the health care sector had four major work stoppages.

Thirteen major work stoppages took place in the private sector. Seven involved health care workers, including a historic 46-day strike involving 5,000 nurses at Providence Hospitals where the Oregon Nurses Association secured substantial wage increases, better staffing plans for patient care, and guaranteed pay for missed breaks or meals. Manufacturing and retail trade had two major work stoppages each.

Major work stoppages took place in 15 states across the U.S. in 2025. The five states with the most stoppages were California (18), Washington (3), Colorado (2), Illinois (2), and Oregon (2). Some strikes took place across state lines: For example, the five-month strike involving 3,200 Boeing machinists occurred in both Missouri and Illinois where the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers secured a 24% general wage increase during the length of the contract.

As noted above, there are limitations to the BLS data, which only include information on work stoppages (both strikes and lockouts) involving 1,000 or more workers and lasting one full work shift between Monday–Friday, excluding federal holidays. For example, the 2025 data did not capture a four-day strike involving 580 hockey players and the East Coast Hockey League because it didn’t meet the size limitations.

Given that a majority (58%) of private-sector workers are employed by firms with fewer than 1,000 employees, these size and duration limits mean that BLS is not capturing many workers who walked off the job in 2025. While BLS shows 30 major work stoppages in 2025, Cornell’s Labor Action Tracker reports 303 work stoppages—298 strikes and 5 lockouts.

Policymakers should strengthen workers’ right to strikeStrikes are a powerful tool that workers can use to rectify the imbalance of bargaining power in the labor market. At a time when affordability and rising income inequality are at the front of workers’ minds, strikes can provide critical leverage to win wage gains, maintain and expand benefits, and improve working conditions. The National Labor Relations Act provides most private-sector workers, whether they are in a union or not, the right to strike. However, bad National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and Supreme Court decisions have eroded this right over time. For example, in NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., the Supreme Court ruled that employers can legally hire permanent replacements for striking workers in some cases.

There is no federal law that gives public-sector workers the right to strike, but a dozen states have extended this right to some state and local government workers. Even with these limitations, thousands of workers across the country and across sectors went on strike to demand fair pay and improved working conditions.

Policymakers—on the federal and state level—should pass laws that strengthen workers’ right to strike. Congress should pass the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which strengthens private-sector workers’ right to strike by eliminating the prohibition on secondary strikes, allowing the use of intermittent strikes, and prohibiting employers from permanently replacing striking workers. Congress should also pass the Striking and Locked Out Workers Healthcare Protection Act, which would prevent employers from cutting off workers’ health care as a form of retaliation, and the Food Secure Strikers Act, which would allow striking workers to qualify for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

State lawmakers should extend full collective bargaining rights, including the right to strike, to all public-sector workers. State lawmakers should also join New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington state in making striking workers eligible for unemployment insurance benefits.

Recent comments