The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Hilary Allen on Fintech Dystopia, is below.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube (video), YouTube (audio), and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

~~~

[00:00:02] Announcer: This is Masters in Business with Barry Ritholtz on Bloomberg Radio.

[00:00:16] Barry Ritholtz: I’m Barry Ritholtz, you’re listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Hilary Allen. She is a professor at the American University, Washington College of Law in DC where she specializes in financial regulation, banking, law, securities regulation and technology law. She published a book, FinTech Dystopia, a summer beach read about how Silicon Valley is ruining things, covering the intersection of finance, technology, law, regulation, and politics. It’s a perfect subject for us to talk about. Hilary Allen, welcome to Bloomberg.

[00:00:59] Hilary Allen: Thank you so much for having me.

[00:01:00] Barry Ritholtz: So fascinating conversation, fascinating topic that you write about. Before we jump into that, let’s, let’s spend a few minutes going over your background. You get a bachelor’s in laws from the University of Sydney in Australia, a master of laws, in securities and financial regulation law from Georgetown here in the States. And you graduated first in your class there. What was the original career plan? Was it simply, I’m gonna go be a lawyer? What, what, what were you thinking?

[00:01:31] Hilary Allen: The original career plan was, I’m just gonna be a lawyer, and then I loved law school and I practiced for seven years and discovered there wasn’t so much law always in the practice of law, and I’m a nerd and I missed it. And so the, the drive was to go back to Georgetown, get my master’s, do some academic writing, and then launch a career as a professor where I could really sort of think slowly about the law.

[00:01:56] Barry Ritholtz: And, and you practiced, you were in London, you were in Sydney, Shearman and Sterling here in New York. Tell us a little bit about the sort of legal work you were doing when you were a practicing attorney.

[00:02:06] Hilary Allen: So basically, there’s sort of two broad categories of the work I did. I did transactional work, banking transactional, typically acting for banks in leverage buyouts. But the work I think I enjoyed more was the regulatory compliance advisory. So there was more law in that, especially when you had new financial laws being handed down in Australia and changes in the US with Dodd-Frank and sort of trying to figure out how to comply with those new rules.

[00:02:34] Barry Ritholtz: So how do you go from practicing bank transactions and some regulatory law to ultimately working with the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission? Tell us a little bit about your experiences there.

[00:02:46] Hilary Allen: So that was a, a series of, a series of fortunate events. While I was doing my masters at Georgetown, I had a professor who was tapped to be on the staff of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, and he pulled me in to work with them two days a week. And we were investigating the causes of the 2008 financial crisis to put together the report that came out, which really was sort of,

[00:03:10] Barry Ritholtz: It’s a nice thick book that they published.

[00:03:12] Hilary Allen: It’s a really thick book with a really thick index even. And the idea was to tell the story, and that’s really sort of stuck with me throughout my career, the importance of being able to explain complex things and how they knit together to cause things.

[00:03:26] Barry Ritholtz: So working with the FCIC, how did that affect how you looked at regulation in general, but more specifically the government’s response to technology, new financial products, the regulatory world in, in general?

[00:03:44] Hilary Allen: So the gift that I got from working with the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission is sort of understanding that there are a lot of things that come together and you need to really look very broadly to understand systemic changes. Another gift that it gave me was, I think, a healthy skepticism of innovation rhetoric, right? Because if you think back to 2008 and what caused it, you know, there were all these stories about, well, these new financial products, these complex new derivatives, we don’t need to regulate them. They’re innovation sophisticated parties involved. We don’t wanna tamp down on innovative potential. And so that, that skepticism has been a helpful skillset as I’ve been navigating the sort of post 2008 financial world where you have the innovation rhetoric from Silicon Valley infiltrating into financial services.

[00:04:34] Barry Ritholtz: You, you raise a really interesting issue that I have to ask about. So how much of what we see is regulation is either an adherence to a, an ideology that sometimes says regulation is good and are guardrails on capitalism. And other ideology says regulation is expensive and anti innovative and reduces job creation. It seems like regardless of the facts on the ground, each side has their belief system. How, how, how do you contextualize that?

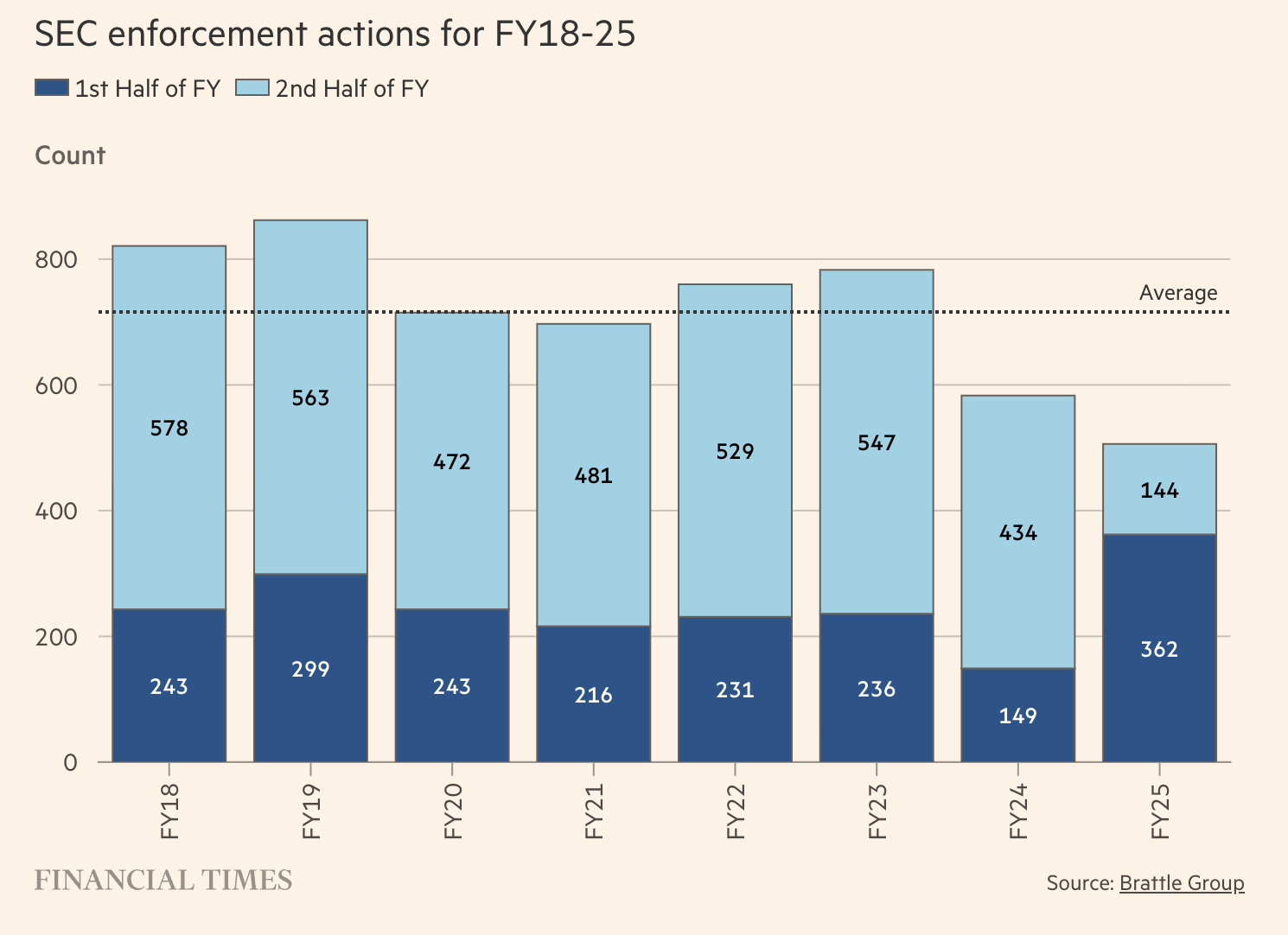

[00:05:12] Hilary Allen: Well, I mean, I think, I don’t think there were too many people in the depths of the 2008 crisis who were saying there’s too much regulation, right? I think it’s a function of where you are in a particular time. I think people’s memories fade really quickly, and as soon as regulation has solved the problems it was intended to solve, or the crisis that spurred the regulation has dissipated, people quickly forget why that regulation is there in place. And then it becomes much easier to see it as something that is just a hindrance, something that is just expensive that doesn’t have a role to play. But I think what we’re actually seeing right at this moment is the erosion of the securities laws that really have stood investors in good stead since the 1930s. Not to say they’re perfect, but the, the general sort of investor protection regime that the Securities and Exchange Commission has always implemented has really encouraged trust in the US stock market. And, and it sort of made it the envy of the world and people wanted to list here that’s really getting peeled back right now. And so I think, you know, it’ll be pretty soon a moment where we realize why we had all that regulation and we’ll miss it.

[00:06:31] Barry Ritholtz: So, so heading into the financial crisis, I recall looking at some of what I called radical deregulation prior. And this isn’t by no means the sole cause of the financial crisis, lots of factors led to this. But you had the Commodities Futures Modernization Act, which allowed what was essentially an insurance product to be issued without any insurance reserves. Seems kind of risky. And then you had the repeal of Glass-Steagall that kept depository banks separate from speculative Wall Street banks. Probably didn’t cause the crisis, but certainly allowed it to get much bigger at, at the, at the very least. And yet there didn’t seem to be any desire after the crisis, Hey, maybe we should put these things back into place. Maybe we should repeal what was added and restore what was repealed. Nobody want, they want to go a totally different direction.

[00:07:33] Hilary Allen: Well, I think, again, this is a story of political economy and there are still a lot of people who are mad at the Obama administration for prioritizing healthcare over financial reform because basically they had one shot at doing something big. And if they had, and I, I’m not weighing in to say that this was the right or the wrong move, but if they had gone right outta the gates with financial reform, I think we would’ve seen more of the bigger structural things that you’re talking about. So, you know, in that immediate aftermath of the 2008 crisis, you had Sandy Weill, who had been the head of Citigroup and had sort of engineered the end of the Glass-Steagall legislation and, and from, this is maybe apocryphal, but apparently he had a, a deal toy that said shatter of Glass-Steagall that he kept on his desk. And again, this may be apocryphal, but I heard that he basically sort of had a conversion after 2008, said, Ooh, yeah, probably shouldn’t have done that. Well,

[00:08:33] Barry Ritholtz: Well a lot of people did. Alan Greenspan famously said, I incorrectly assumed people’s concern over their own reputation would’ve prevented some of the excesses we’ve seen. I’m paraphrasing, but that was pretty close to what he said.

[00:08:46] Hilary Allen: Yeah. He said the world sort of didn’t work the way I thought it did. And I think, you know, had they gone straight outta the gates with financial reform, you might have seen some of that structural reform. But by the time they got around to it, you know, Dodd-Frank wasn’t passed till 2010. Right. You know, then, then the political economy calculus had shifted. The industry was in more of a position to sort of argue for weaker rules and, and fewer structural changes. It

[00:09:11] Barry Ritholtz: It’s amazing how rapidly memories fade and people just quickly, oh no, that was then now it’s new. You’ve worked inside the global financial system as well as studying it from the outside. How did being part of the FCIC affect how you perceive technology, new financial products, regulation and deregulation? How, how did that affect your, your perspective?

[00:09:38] Hilary Allen: You know, I didn’t think a ton about technology at that time. That’s sort of been a later addition to the work that I do. But the broader themes of financial innovation regulation, deregulation, you know, I see the value in financial stability regulation in particular. So financial stability regulation are the rules that are supposed to prevent financial crises. And they work often sort of hand in hand with investor protection regulations, but they also aim to do something differently. And part of the challenge when you’re trying to prevent a financial crisis is this silo mentality where people just think about their own little piece of the world and okay, we can deregulate our little piece and we don’t, won’t think about the flow on consequences and what, what incentives it’ll create, et cetera. And so, you know, my real takeaway was always to have the most holistic perspective possible to break down that silo mentality. And later in my career, that meant learning about the new technologies that are sort of infiltrating the, the financial system. So,

[00:10:42] Barry Ritholtz: So I want to talk about technology and I want to talk about FinTech Dystopia, but there is a quote from within that that applies directly to what you’re describing with stability, which was it’s the economic precarity, stupid, paraphrasing James Carville. Tell us a little bit about the economic precarity.

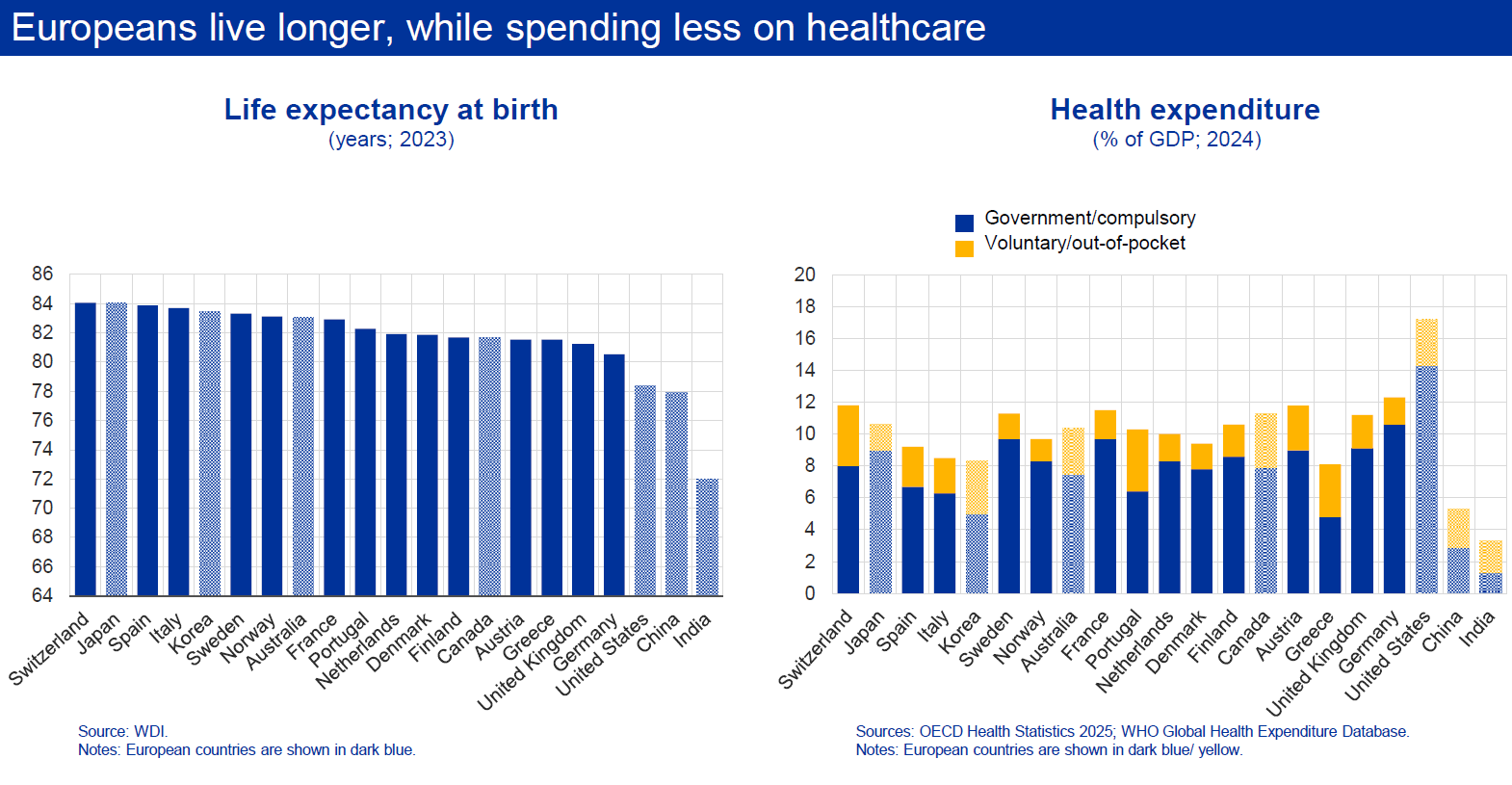

[00:11:03] Hilary Allen: Yeah, so I think a mistake that we have made collectively in recent years is to say, well, look, the economy’s doing well, everything’s fine. And that really doesn’t, you know, mesh with many people’s experience of the economy. So it used to be, well, probably not always the case, but closer to the case in, in the Clinton years where there was less economic inequality than there is now, that you could sort of say a rising tide lifts all boats. But now what we’re seeing is over half of Americans live from paycheck to paycheck, even in a good economy, right? And so in that kind of circumstance, the financial system’s not, and the economy aren’t working for everybody. And so I think when we think about what we’re trying to achieve with our financial system, it should be that we are trying to find a solution to this economic precarity. And also that begs the question of whether the financial system in and investing is actually the way to get there. And maybe we need broader public policies to address that economic precarity so that no one, or at least not half of the population are just scraping by.

[00:12:18] Barry Ritholtz: So we just passed a new set of laws that include thousand dollar accounts for, for newborns. Isn’t that gonna solve financial inequality? All these kids, by the time they’re 30, they’ll be worth millions.

[00:12:35] Hilary Allen: I think you might need to offset against the people losing their health insurance subsidies. I don’t think that a thousand dollars gonna go very far.

[00:12:41] Barry Ritholtz: Right. And, and what’s fascinating is watching just the parade of billionaires come out and no, no, we need to supplement that thousand dollars. So first it was Michael Dell, and then it was Ray Dalio. I don’t know who else is gonna step forward, but it appears, hey, we’re not really paying a whole lot in taxes. We might as well throw some money at some, some babies. That seems to be the philosophy.

[00:13:05] Hilary Allen: Yeah. I mean, I don’t love philanthropy in that sense, supplementing democratically sort of elected policies, you know, it, it, it gives a lot of sort of discretion and power to people as to how they wanna distribute their largesse to, to some degree that’s fine. But again, when we have a society where half of the population is barely scraping by, I don’t think their livability should be predicated on the whims of billionaire largesse.

[00:13:33] Barry Ritholtz: Fair, fair enough. You, you talked about technological innovation. In your book you argue that financial technology innovation is driven largely by legal design rather than technical brilliance. Explain that a little bit. What, what is it about FinTech that seems to be working the perspective from an attorney rather than an engineer?

[00:14:00] Hilary Allen: Yeah, so this was something that, as I said, I came to a little later in my career. I think earlier in my career when I first started looking at FinTech, I generally accepted, you know, the party line. This technology is revolutionary, this technology is making things more efficient, this technology is fixing things. And then I realized that the people who were saying that had something to sell, and I probably should learn a little more about the technology because if you wanna work on financial regulatory policy, now you need to understand the extent to which the technology actually lives up to what is claimed it can do. And so, sort of my first sort of foray into this was, I’ve looked really in detail at blockchain, which is, is truly frankly a terrible technology. It’s a clunky database. And, and, and it’s not something you would ever choose for any kind of financial market infrastructure, but for the fact that it’s been very easy to convince regulators not to regulate it. And so the value add that comes from crypto has never been blockchain technology as a technology. It’s been whipping up stories about that technology that have justified avoiding regulation. And we see it in other instances as well. You know, there are FinTech lending that is replicating some of the, the predatory payday lending that we’ve seen before.

[00:15:22] Barry Ritholtz: The buy now pay later sort of financing or, well,

[00:15:25] Hilary Allen: The payday, payday loans have been around a lot longer than that. This is sort of a, it’s like a $400 loan that you get to bridge you over till your next payday. And you know, there’s been a lot of predation in that market and some states had banned those, those products. Essentially,

[00:15:43] Barry Ritholtz: You, you think 29% interest is not fair. You have a problem with that. We’re just trying to make a profit here.

[00:15:50] Hilary Allen: Some of these interest rates are 300%.

[00:15:52] Barry Ritholtz: Get out. Yeah. That’s in, and, and what is New York top out at like 19%? Something like that?

[00:15:58] Hilary Allen: I, I don’t know about New York. Yeah. But, but, but

[00:16:01] Barry Ritholtz: Normally anything, you know, mid double digits is, is thought of as luxurious. 300% is just next level.

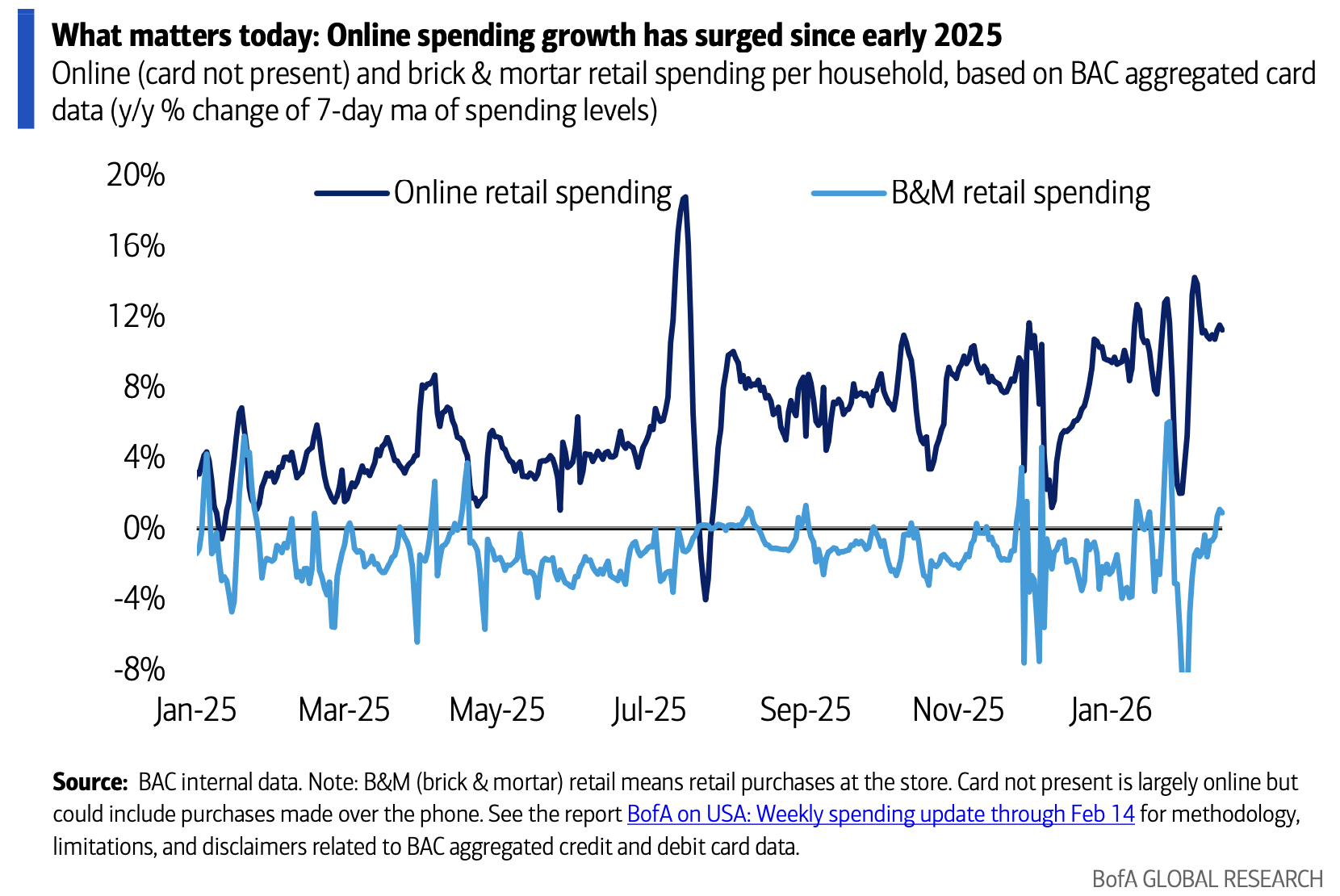

[00:16:08] Hilary Allen: Yeah. I mean they’re not, it’s not set as an interest rate per se, they’re fees, but once you actually convert that into a, a per annum, they can be in the hundreds of percentages. And so that has always been a problem. And we’ve had states act and then we’ve had new FinTech lenders saying, well actually we’re different from payday lenders ’cause we use AI to screen our borrowers, and so you should treat us differently. And yet they’re charging interest rates that are equivalent to what payday lenders do. And then you mentioned buy now pay later. Again, they say, well we’re, we’re not even extending loans. This isn’t a loan at all, so we shouldn’t have to comply with the laws around lending, around disclosure around that kind of

[00:16:45] Barry Ritholtz: Thing. How is that not a loan? You’re buying a product that you don’t have money for? Someone is paying for that. Isn’t that a loan?

[00:16:54] Hilary Allen: I would say so.

[00:16:56] Barry Ritholtz: Okay.

[00:16:56] Hilary Allen: But, but

[00:16:57] Barry Ritholtz: How, what, what’s the counter to this isn’t a loan, this is a, a pre layaway,

[00:17:03] Hilary Allen: Essentially. Yeah, no, we, you know, we, we, we don’t charge interest. There are late fees if you don’t pay, but that’s not the same as interest. You know,

[00:17:10] Barry Ritholtz: That’s fair. Like we, we, we bought a couch no interest for six months. So as long as you pay it off within six months, that sort of thing seems to be interest free.

[00:17:22] Hilary Allen: But then when you look at the business model and you see that a significant chunk of the people are incurring these late fees, then well,

[00:17:28] Barry Ritholtz: That’s their fault, isn’t it? That’s human nature. We, you can’t blame us if we take advantage of people procrastinating and not paying off their fees in time. Well,

[00:17:38] Hilary Allen: It’s not that they’re procrastinating, it’s that they’re choosing between paying rent or paying this off. So this is

[00:17:43] Barry Ritholtz: Food. Yeah. Medicine.

[00:17:45] Hilary Allen: Exactly. So this, this is coming back to, it’s the economic precarity stupid, right? If people are in these dire straits, we should not be surprised that FinTech firms are trying to capitalize on that and profit from it. Which is why I think, you know, what we need are some kind of public safety nets to, to sort of make and, and a higher minimum wage and higher social security benefits.

[00:18:10] Barry Ritholtz: Coming up. We continue our conversation with Professor Hilary Allen discussing her new book, FinTech Dystopia, a summer beach read about Silicon Valley and how it’s ruining things. I’m Barry Ritholtz, you are listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. I’m Barry Ritholtz. You are listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Hilary Allen. She teaches at the American University Washington College of Law in Washington DC where she specializes in regulation of financial and technology laws. So, so let’s talk about the digital only book. Ironic, right? FinTech Dystopia where you describe modern financial technology simply as Silicon Valley ruining things. Explain that. Seems like an extreme example. And, and give us some examples of how Silicon Valley is ruining things.

[00:19:27] Hilary Allen: So just to be clear, not all modern technology is ruining things. There’s a particular business model approach that I think is ruining things and that is derivative in many ways of the venture capital model in Silicon Valley.

[00:19:40] Barry Ritholtz: Venture capital.

[00:19:41] Hilary Allen: Just venture, okay?

[00:19:42] Barry Ritholtz: Yep.

[00:19:42] Hilary Allen: Venture capital model in Silicon Valley. So it’s sort of got this sheen around it that’s iconoclastic and they, they make bets on these moonshots that’ll, you know, save all of humanity and yada yada yada. But in fact it’s, it’s pretty well established as a playbook at this point. You know, there’s a lot of subsidies that go to venture capital by virtue of their having access to pension funds by virtue of sort of capital gains taxation. And so they’ve got sort of, and and especially in low interest rate environments, they attract a lot of money. So they have pretty cheap money available to them, and then they go shopping. And what they go shopping for is not the iconoclastic sort of outlier that we think of, but what we’ve seen and what the evidence shows is that they tend to go shopping for the same things that their friends are going shopping for and they go shopping for the businesses that their friends have developed.

[00:20:36] Hilary Allen: And so there’s this sort of very, sort of insular mentality in what they’re looking for. And they’re also looking for something that they can cash out of very quickly because the, you know, the average venture capital fund has a, what, a 10 year, sometimes 12, but usually 10 year duration. That’s really not that much time to find something to invest in, have it grow and then cash out. And so they’re not looking for things that are going to take decades to develop. They’re looking for things that they can grow quickly and get out of in about five or six years.

[00:21:09] Barry Ritholtz: So give us a few examples. What do you think is this sort of, you know, not adding a whole lot of value venture backed businesses?

[00:21:19] Hilary Allen: So not intentionally, but it just turned out that way as I wrote this, this book, almost every FinTech business I looked at had been funded by Andreessen Horowitz. They had been sort of the lead. So, you know, they, they,

[00:21:33] Barry Ritholtz: They’re the hot VC these days. I, I’ve, full disclosure, I’ve interviewed Andreessen, I’ve interviewed Kaur, I’ve interviewed Horowitz. So I’ve sat with them and talked about a lot of their businesses. But the past few years they’ve been very front and center, very active. Yeah,

[00:21:51] Hilary Allen: No, and they sort of, they have their, as a marquee name as you said, they’re the hot VCs. Once they say they like something, they can basically attract other venture capital to those, those businesses. And so they’re essentially taste makers,

[00:22:05] Barry Ritholtz: Which, which is fascinating you say that. ‘Cause before that it was Sequoia, before that it was Kleiner Perkins. Like, you work your way, there’s a hot firm for a decade. The nineties had it, the two thousands had it, the 2010s had it. They tend not to maintain that position forever. Although to Andreessen Horowitz’s credit, they’ve been the it girl for a good, good run so far.

[00:22:29] Hilary Allen: Yeah. I mean I wouldn’t say that that’s a good thing, but yeah, so, you know, they, they basically built the crypto industry. So, you know, we, we, the, the narrative around crypto is this organic sort of community of cyberpunks and libertarians. But, but they really built that industry. They were early investors in Coinbase. That was their first crypto investment. And then they have plowed a lot of money into the industry and it’s sort of, their seal of approval has been what’s attracted people to it. And you know, part of what Andreessen Horowitz does is it doesn’t just invest, it does aggressive marketing campaigns for the things that they’ve invested in, aggressive lobbying. So they’ve really been at the forefront for trying to get the laws changed to accommodate their business models. So yeah, there’s, there’s crypto, but they’ve also been at the sort of the forefront of, I always, there’s one of the do not pays, I think it’s a firm that’s theirs. I always get mixed up. They, they were very early investors in Robinhood, the FinTech trading stock app, which

[00:23:39] Barry Ritholtz: Originally started out as a stock app and then it became eventually a crypto app and now it’s a bet on anything app.

[00:23:46] Hilary Allen: Yeah. And again, that is a company that by the time it IPO’d had racked up all kinds of fines from the SEC and FINRA because it was violating laws left, right and center. You know, it was one of the first to offer commission free brokerage. Right. But as the chestnut goes, if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. And it makes most of its money from payment for order flow and was not clear with its customers in the early years about that, how that was going on and how they get paid a lot more for your options trades than your regular stock trades because more

[00:24:28] Barry Ritholtz: Profitable.

[00:24:28] Hilary Allen: Yeah. More profitable for the Citadel Securities of this world to, to take those. Yeah.

[00:24:33] Barry Ritholtz: Huh. Really kind of interesting. And yet at the same time you have a chapter in your book, Silicon Valley Welfare Queen, explain, I thought that these are, you know, Ayn Randian libertarians that don’t wanna suckle off the teat of big government. And these are people that are builders and self-made people. You’re arguing not so much.

[00:25:01] Hilary Allen: Well, they don’t want us suckling on the teat of the state because they might have to fund that with taxes, but, but they’re okay suckling themselves.

[00:25:08] Barry Ritholtz: Right. So, so give us a few examples what companies started out as welfare queens.

[00:25:14] Hilary Allen: Well, I mean, again, the, the whole story of, of tech, the, the internet and smartphone boom is very much based on technologies developed by the government.

[00:25:25] Barry Ritholtz: DARPA and the whole internet.

[00:25:26] Hilary Allen: Exactly. And you know, and, and I think if you look at the iPhone, a lot of the individual technologies that went into that, again came from everything.

[00:25:34] Barry Ritholtz: With microwaves comes outta NASA, right? Yeah.

[00:25:37] Hilary Allen: So, you know, first of all, this, this entirely self-made story falls apart right there, because as I mentioned earlier, if you’ve only got six years to turn around a technology, you’re not really investing in prototypes. In thinking really hard about physical hardware and how that works, you’re really looking for a software thing that you can gin up pretty quickly. And so the really long-term investment comes from the state and, and has always done. And then it’s commercialized, you know, and I think that that sort of has worked well except that you get to the point where the, you know, the venture capitalists who are commercializing are saying, well, we shouldn’t have to pay any taxes to fund the state that develops these technologies. They also benefit, as I said, enormously from laws that they lobbied for in the late seventies, I believe changes to ERISA, which allowed pension funds to invest in venture capital, basically didn’t exist before. Hmm. And at that same period, they were lobbying for changes to the capital gains taxation.

[00:26:42] Barry Ritholtz: Well you have the carried interest loophole. Exactly. Which continues to persist. I’m drawing a blank on the author’s name. There’s a book, Americana, 400 years of technological innovation that makes the argument you’re making go back to the telegraph funded by Congress, go back to railroad, like every major technological innovation or most major innovations got seeded with the government and then eventually the private sector takes over. And what has changed in recent years is that public private partnerships seems to have broken.

[00:27:20] Hilary Allen: Yeah, actually, so the book I really like on this is Margaret O’Mara’s book The Code, who does, she does a great history of Silicon Valley. And yeah, I think the, the understanding that there was a quid pro quo has sort of fallen away. So always the private sector has commercialized this, this technology, but if we have an unwillingness to sort of pay any taxes, if we have an unwillingness to invest in government capacity to invest in universities where so much of this stuff is developed, you know, you take Marc Andreessen, he, you know, he got his start because he was lucky enough to be a student at the University of Illinois at the time where they had a special grant to look at the beginnings of the internet. He worked on a team there that developed a prototype internet browser and then he went into the private sector and they let him build one from the private sector and that was Netscape and that’s how he made his fortune. So he was sort of in the right place at the right time to take advantage of public investment in this kind of thing. And yet this is the kind of thing that we’re seeing that these leading venture capitalists wanna shut down.

[00:28:36] Barry Ritholtz: Huh. Really, really interesting. Since we’ve been talking about books, you’ve, you’ve criticized Abundance, which is by Derek Thompson. And Ezra Klein has, the whole concept of abundance is sort of a sexy way to make excuses for techno solutions. Tell us a little bit about that.

[00:28:55] Hilary Allen: Yeah, so this is, this is something I get into a lot of conversations with people these days because I think there are some elements of the original sort of abundance agenda that are very appealing to people in terms of, for example, increasing housing capacity. And I, I do think that that is something that needs to happen and has to be done in the right way. But if you look at who is funding the abundance movement, they have conferences, et cetera, it is Andreessen Horowitz and other people from Silicon Valley. And it seems to be this attempt to essentially put a, a happier face on the deregulatory project that Silicon Valley is looking for to sort of make it seem kinder, gentler and more progressive. Because the abundance movement is sort of in a nutshell is supposed to be, well we shouldn’t have artificial scarcity, we should build more of what we want to do, that we should take away some of the roadblocks that are getting in our own way. And when you say it like that, it’s sort of hard to disagree with, well

[00:29:55] Barry Ritholtz: That works for housing. You, you have NIMBYism with housing, but when you take that away, it also means you’re gonna end up with perhaps high rises or multifamily units in a suburban area that some people don’t want in their neighborhood. There’s always a series of trade-offs with people who are already there versus people want to get there. What is the specific problem with abundance as a philosophy towards building more of what we want as a society?

[00:30:27] Hilary Allen: Because it’s who gets to decide what more of what we want is. And if you look at who’s funding the abundance agenda, it is the billions of the tech elite. And these are people who have really shown that they are quite willing to run roughshod over regulations that are there to protect the public from harm if that enables them to profit. And so I am just skeptical that a movement that is funded by these people is really going to be prioritizing the kinds of projects that would benefit the economically precarious. I think it’s more likely that it’ll be benefiting themselves and will lose protections for people with less voice that are currently in place.

[00:31:08] Barry Ritholtz: So what sort of overhyped products do you think best explain the problems with this approach? Like what are these companies putting out that either is a result of regulatory capture or just don’t do what they promised? ‘Cause you would think that in the world of venture, either your product finds an audience, it finds a customer base or it doesn’t and fails and that goes outta business.

[00:31:37] Hilary Allen: Yeah. So that’s sort of the perverted part of this is that that market logic, like, you know, survival of the fittest because of all the subsidies that benefit venture capital, that doesn’t really apply that logic anymore. So, you know, give

[00:31:50] Barry Ritholtz: Us an example.

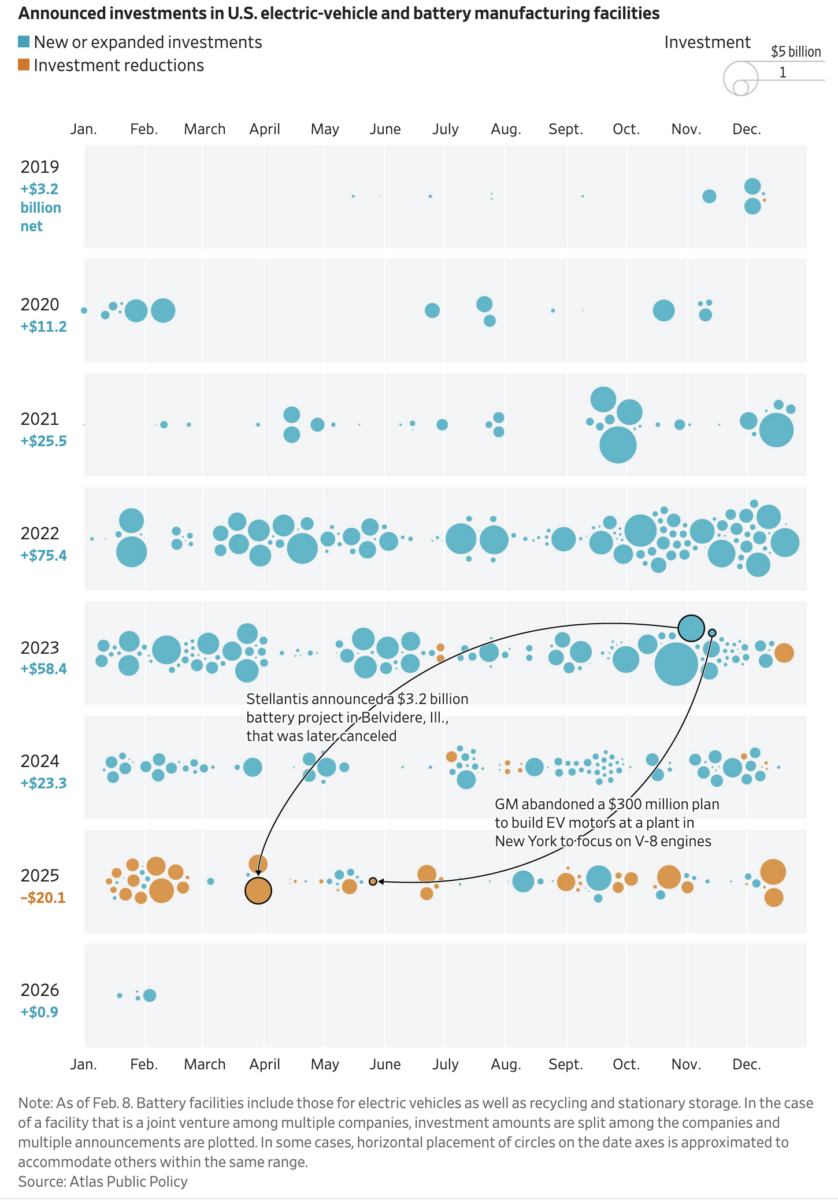

[00:31:51] Hilary Allen: Crypto, crypto should have died many times already. Particularly it should have died in 2022. When we had the big crypto winter at that time, particularly Andreessen Horowitz crypto had this huge war chest of funds that they had raised and they stopped investing in crypto startups at that point because, you know, everything was done. But what they started using that money for was lobbying political spending. And they really worked very hard on members of Congress to essentially create laws that would allow the crypto industry to keep doing what they’re doing, which was not allowed under the securities laws as they were. So the whole business model was regulatory arbitrage. They wanted laws that would sort of give a patina of legitimacy and hopefully encourage institutional investment, attract more money to the space, but not actually make them have to, for example, like Coinbase combines the functions of a broker dealer and an exchange that’s not allowed in securities. You can see why there’s all kinds of conflicts of interest that come,

[00:33:02] Barry Ritholtz: Right? Either you’re an exchange or a brokerage firm, not both.

[00:33:05] Hilary Allen: But in crypto you’re both right. And so if you applied the securities laws to crypto, they would have to disaggregate and basically would probably destroy their business model. So what they wanted was a law that said, no, it’s fine, crypto special, you do both. And so that, that really an industry that should have failed is, you know, again, rising, being propped up all through this sort of aggressive political spending. And, and I mean, I’ve talked to people in Congress off the record who have said that they’ve only voted for these laws because they’re afraid that if they don’t, that crypto industries will target them.

[00:33:48] Barry Ritholtz: Hmm. What other products do you think are, are overhyped and, and fail to satisfy their markets?

[00:33:55] Hilary Allen: Well, right now the obvious answer is a lot of the AI products, the anything sort of, it, it’s hard when you talk about AI because it’s such an umbrella term for so many different things, right? I

[00:34:06] Barry Ritholtz: I have Perplexity on my phone. It, it does a better job with search than Google does. I get better, more comprehensive answers. What’s wrong with AI?

[00:34:18] Hilary Allen: Well, let me disaggregate it first because there’s plenty of AI that there’s nothing wrong with, right? So AI is not intelligent in any way, shape, or form, right? It’s a marketing term. What it is is it’s an applied statistical engine. You have an algorithm that looks for patterns in data and then acts accordingly. And that kind of technology has been around for a long time. It does. Like for example, it’s great for fraud detection in a bank for credit card transactions for example. So that, you know, that’s, that’s an A plus use of, of AI. But the last few years everybody has been pouring everything they’ve got into these LLM based tools, these large language model based tools. So these are tools that can, you know, old AI tools would just sort of classify something, put something in a group or, or predict something. But, but now we have these tools that generate content, particularly text, but also, you know, video, music, et cetera. And there are so many problems with this technology because it’s being sold as technology that can replace humans, right? That that can basically, it’s worth throwing trillions of dollars into this because of the productivity gains that will get by firing all the humans, essentially is, is the story they’re telling. First of all, that would be great,

[00:35:40] Barry Ritholtz: Right? That’s a problem in and of itself. The, the way I have heard it described that’s a little less catastrophic is this is gonna make everybody more efficient, more productive, it’ll make companies more profitable and we’ll all be able to do more with our existing staff than having to go out and hire hundreds of more people.

[00:36:06] Hilary Allen: But that is not true, sadly. That’s the pitch line, right? So these, these tools make a lot of mistakes. You know, even the very best ones make mistakes. It’s,

[00:36:17] Barry Ritholtz: We, we’ve seen a lot of attorneys, you and I are both attorneys, a lot of judges have been calling out attorneys who theoretically are supposed to be doing this on their own and instead are outsourcing it to AI and all of its hallucinations and citing cases that don’t exist. The assumption is that’s gonna get better eventually.

[00:36:37] Hilary Allen: But it won’t. So this is, this is the problem. But it won’t, but it won’t. So these things are statistical engines, right? They, they can’t check for accuracy ’cause they don’t understand accuracy as a concept, right? There’s no reasoning. It’s, it’s literally, the, the most statistically most likely word after the last word I gave you is this word. There is no way to make that care about accuracy. ‘Cause it’s, it’s, it’s not a, it’s not a thinking machine. And I think there’s increasing acceptance that these, these models have hit a wall and they are as accurate as they are going to get. Really?

[00:37:15] Barry Ritholtz: Yeah. That’s kind of, that’s kind of fascinating. My concern was, at least on the legal side, hey, you have this existing body of work and all this research and brief writing and arguments that exist as of now, if you’re gonna replace people from doing that, are you gonna freeze the state of legal knowledge at 2026 and five or 10 years from now? If you don’t have people writing these briefs, you don’t have people writing these decisions, how can AI respond to what’s taken place over the past 10 years if we don’t have the humans actually doing the grunt work?

[00:37:51] Hilary Allen: Yeah, I mean there’s a, there’s, I mean I think those kinds of concerns have been expressed very much in the cultural context. You know, if, if, if we disincentivize creators from making new music and new art or is this it, are we stuck with, with what we’ve got with something like the law? One of the challenges is that, you know, these large language models, they don’t get updated on a day-to-day basis. You know, there’s, there’s sort of a stop point and then they, they don’t know, well they don’t know anything that they don’t have the data from after a certain date. So that, that’s a limitation. But the thing I worry most about with the law is that you have to be able to spot the hallucinations or you’re gonna get yourself in very big trouble. And I think this is true for a lot of different fields.

[00:38:40] Hilary Allen: And, and this is again just to digress a little, why the, the profitability narrative is not true, right? Because the only place where you can just put this content out and just leave it there is in very low stakes places, right? Where it doesn’t matter if you get something wrong, but even, you know, things that you wouldn’t think are such a big deal have proved to be quite high stakes. So Air Canada had a chatbot that told a customer that if they wanted to apply for a bereavement discount for a flight, they could do that after their flight was done. Now that’s not Air Canada’s policy. They, you had to do it in advance. And so this customer tried to get their refund after the fact. And Air Canada said, well the chatbot got it wrong. Too bad. So sad for you and it’s your

[00:39:27] Barry Ritholtz: Chatbot, you own, you are responsible for it. Exactly. Not, not my mistake. Your mistake.

[00:39:31] Hilary Allen: Exactly. And so even in these sort of reasonably low stakes customer service interactions, there’s reason to be really worried about inaccuracy. Now you start dialing up to things, to medical advice, legal advice, you know, it’s just you, you can’t rely on them. And I worry that we’re putting people in a very difficult position because it’s a, it’s a lot easier to get something right when you write it yourself than it is to find mistakes in something someone else has put together. Right? So

[00:40:01] Barry Ritholtz: Let me push back a little bit ’cause I’ve been watching the AI reading medical scans and at some point last year, or maybe it was two years ago, the, the technology theoretically passed the accuracy rate of humans, fewer false positives, more identifying missed negatives that should have been positive than people. Is, is that not accurate or where, where are we with, with the medical application of that?

[00:40:37] Hilary Allen: So this is why I think it’s so important to disaggregate the different kinds of AI because that is not sort of LLM based AI and some, as I said, some of those tools are great, I can’t weigh in on medical imaging and things like that. So it may very well be the case. What I’m talking about is, you know, what, if you’ve got, you know, a doctor coming up with instructions for a care plan for their patients and they let the AI do it, right? If there’s a mistake in there, they’re much less likely to catch it. If the AI, because you, you know, you know how things go, you’ll be expected to look at more of these ’cause you’re not generating them yourself. Right? And it’s always easier to get things right when you do it yourself than when you’re reviewing someone else. I mean, when we were lawyers, we used to, that’s why you wanna have the pen on contracts. You wanna, you wanna hide things from the other side and now it’s, now it’s the AI hiding stuff from you. And I worry that especially with younger lawyers coming up through the ranks who are encouraged to rely on these tools from the beginning, who won’t actually develop the skills because you, you don’t learn well when you sort of don’t process it yourself. So if you’re, you spent your whole career using AI, you’re not gonna be able to spot the problems in the AI and

[00:41:53] Barry Ritholtz: The, you’re not gonna have the skillset.

[00:41:55] Hilary Allen: No. And so then I’m worried about, you know, those young lawyers getting sued for malpractice because they missed something that the AI generated, but they were never even given the opportunity to learn how to spot it themselves. It’s,

[00:42:06] Barry Ritholtz: It’s a problem with the rungs on the ladder being removed, especially we see that now manifesting itself, the unemployment rate of the under 30 is about double what it is for the national unemployment rate. And I can’t help but wonder how much of that is somehow related to the proliferation of AI tools for white collar jobs.

[00:42:30] Hilary Allen: I think, you know, Cory Doctorow who does a lot of work in the tech space, has a great quote on this that I’m gonna butcher a little, not say it quite as well as he does it, but he said the AI can’t do your job, but the AI salesman can convince your boss to replace you with AI that can’t do your job. Right. So it’s, I think you’re right that there is at this moment a, you know, a, I mean it’s also hard to say how much of this is AI washing as opposed to real AI displacement, right? The economy’s not in a great place right now. People don’t wanna hire anyway. It looks a lot better if you say, well we’re not hiring ’cause we’re replacing them with AI than just, huh, we’re having a rough time. We’re not hiring.

[00:43:14] Barry Ritholtz: AI washing is a, a phrase I haven’t heard used in modern parlance yet, but it certainly makes a whole lot of sense. The line I heard, and I don’t know where I’m stealing this from, is you’re not gonna be replaced by AI. You are gonna be replaced by somebody with a greater facility working with AI than you have. And it sort of creates a self-fulfilling arms race to make sure you, you learn how to use that tool. Otherwise you’re at risk for being replaced by somebody who knows how to use that tool.

[00:43:44] Hilary Allen: I’ve heard that too, but I don’t think these tools are that hard to use, right? I mean, that’s a failure on the part of the AI companies if they’re so hard to use, right? It wasn’t hard to use Google search.

[00:43:54] Barry Ritholtz: Perplexity and, and even ChatGPT is, is absolutely easy as pie to use. I don’t, I don’t find them difficult. Sometimes you have to keep changing the prompts to get an improved answer. Like if you just ask a question and walk away, well then you’re getting what everybody gets. But if you, I, I don’t, I don’t really buy into the prompt engineer job title, but a little exposure is the more you ask it and the more you vary it, you get a variety of answers and eventually you come up with something, oh, that’s interesting and different. Let me, let me take a look at that.

[00:44:31] Hilary Allen: So I, I mean I have strong feelings about this as an educator because if these tools are worth their salt, it shouldn’t take our students long to figure out how to use them, right? Right. So why are we bringing them into education where what they really need to learn is how to spot hallucinations, how to think critically so that if they are going to use these tools later, they can use them to the best of their abilities. This whole arms race sense of, well they need to use them in school so they don’t get left behind. I’m like, it, it didn’t take long to learn how to Google, they’ll be fine.

[00:45:01] Barry Ritholtz: Hmm. You’ve been pretty critical of things like crypto and stablecoin. We’re going to get to those in a moment. I wanna talk about some other things you’ve discussed. You’ve brought up the whole idea of technology as a branding exercise. Phrases like democratizing finance, disruptive technology, banking the unbanked. You’ve described these as just, you know, marketing and not really accomplishing anything. Tell us a little bit about those and, and give us some examples.

[00:45:38] Hilary Allen: Sure. I mean, I think at the heart of all this is, is innovation speak and innovation worship, right? When we alluded to that earlier, the sense that anything that is innovative is inherently good and must therefore be permitted at all costs. And that is sort of the font of a lot of the rhetoric and narrative that we get out of Silicon Valley that ultimately is there to attract funding, yes, but also to procure legal treatment that facilitates what they wanna do. It, it actually creates often an unlevel legal playing field where you have the incumbents who have to comply with all the laws and then the disruptors, as you say, who don’t have to comply with all the laws and can succeed on that basis, even if their product isn’t superior in the way we would typically expect a disruptor’s product to be. So yeah, I mean, disruptive innovation, you know, goes back to Clayton Christensen and, and the Innovator’s Dilemma, this sense that if you, if you stay still and just make good products, you’ll be outcompeted by someone who is trying to do things a little differently. But you know, there, there’s no real formula that you can take away from that as to what, you know, disruptive is in the eye of the beholder.

[00:47:00] Barry Ritholtz: So, so let me push back on that a little bit. And all my VC friends, I could just hear their voices in my head and the pushback is, look, most new companies fail. Most new technologies crash and burn. Most new ideas never make it. And even the best of the best VCs, they’ll make a hundred investments for that one moonshot that works out. And most of the other 99 are at best break even, but mostly losers. How could you say this is true? Oh, and real innovation often finds itself in between the regulatory regime because the technology that’s being created was never anticipated by the regulators or, or anybody else. Fair, fair pushback.

[00:47:51] Hilary Allen: A lot of points that I would quibble with there. Some’s fair, quibble away, quibble away. Alright, so there’s this idea that the law is a barrier to innovation because law is old and innovation is new and the law couldn’t possibly have contemplated the innovation. The story about the innovation is what makes it new, right? Most of the things that we’re seeing in the FinTech space, they’re not that new, right? As I said, you know, we’ve got FinTech lending has a lot of the things that we didn’t like about payday lending, right? Why shouldn’t the laws from payday lending apply? Crypto, basically, I mean the, the crypto markets for all the world looked like the stocks and bonds in the unregulated markets of the 1920s. We saw how that ended. They ended in such a spectacular crash that we ended up with the securities laws. Why shouldn’t they apply?

[00:48:39] Hilary Allen: What’s, what’s so different, right? So this construction of novelty is something that is done intentionally as, as a narrative. Now I fully appreciate that we need the optimists in this world who are gonna try new things. And, and, and I say that very early on in the book, the people who these stories are useful because they attract funding to new things. So I’m not saying we should do away with it completely. My argument is that the, the yin and yang, the balance between the optimists and the realists is badly out of whack because we give so much deference to the stories about innovation, about disruption, about how technology can solve problems that have been with us for centuries. We can magically get rid of intermediaries now with blockchain technology apparently, except

[00:49:30] Barry Ritholtz: We can. Well that was one of the, that was one of the story narratives was disintermediation and until it no longer was the story, but, but let’s talk about some specific companies that you’ve mentioned that you’ve written about, and I, and I wanna get your sense on it. And, and the oldest one was PayPal. To this day. And, and I was a PayPal user back in the 1990s with eBay and those sort of things. To this day, I don’t understand what they did that was any different than a credit card other than being a bit of middleware that eventually became a rentier. Why not just use a credit card? Why do I need PayPal between me and Amazon or me and eBay?

[00:50:16] Hilary Allen: So this is really an interesting story and I learned a whole lot about this in research for this book by reading Max Chafkin’s book, The Contrarian about Peter Thiel and the start of the beginning of PayPal. And in fact, the idea for PayPal came from the same place that the idea for crypto has come from, which is this, this techno libertarian idea of we don’t like regulation, we don’t like central banks, we would like to have private money and we would like technology to help us have private money. And PayPal wasn’t the only one of these kinds of startups back in the early .com bubble. So PayPal I think succeeded because it sort of lucked into this deal with eBay, as you said, right? It, it sort of had no distinguishing features as far as I can tell that made it any superior to the Beans and the Floos of this world. It lucked into this deal with, with eBay. And so,

[00:51:13] Barry Ritholtz: And eventually eBay buys them to solve their, I guess, credit card management problem. I don’t really understand. Yeah. I still, you know, 20, 25 years later, I still don’t understand why they were necessary.

[00:51:28] Hilary Allen: I think, yeah, I mean my, my knowledge of this comes primarily from reading Max Chafkin’s book, which I highly recommend, but that’s, that’s my understanding too. And so, you know, they are a payments technology. I too struggle to sort of understand what they offer that a credit card doesn’t in many ways. One thing they are though is they are sort of the OG regulatory arbitrage story in FinTech, right? So, you know, I’ve said so much of FinTech is actually about arbitraging the law rather than technological superiority. PayPal from the beginning was flaunting quite aggressively the banking laws because only banks are allowed to accept deposits and people were keeping money in their PayPal wallets and for all the world that looks like keeping a deposit. Peter Thiel from the beginning was very aggressive on the lobbying to make sure that that was not considered deposit taking. Early on, there were multiple states that were investigating it because they thought it was the unlawful taking of deposits. He lobbied heavily in Congress and lobbied heavily at the FDIC and ultimately, you know, that worked. And so I think that has sort of been the prototype, that blitzscaling prototype. I think people perhaps underestimate the degree to which blitzscaling is really about playing it on an unlevel legal playing field.

[00:52:54] Barry Ritholtz: Let, let’s talk about stablecoins. What sort of value do they provide?

[00:52:59] Hilary Allen: Again, unless you are trying to do illicit transactions or gamble, not a whole lot, right? So,

[00:53:05] Barry Ritholtz: Well, a stablecoin is worth a dollar and it promises to always be worth a dollar. Don’t we have dollars? Why do I need a stablecoin?

[00:53:13] Hilary Allen: Well, you need a stablecoin often to do illicit payments. So if you want, you know, if you’re, they’re, they’re very popular, for example, with all kinds of drug cartels and they’re good for sanctions evasion. They’re also very good if you want to gamble in crypto and you wanna use it as sort of a cash management tool in between crypto investments, kind of like a money market mutual fund in your brokerage account for parking funds in between crypto gambling, but they’ve really never had any utility in any big way as a legal payments mechanism.

[00:53:48] Barry Ritholtz: Alright, so what about, you mentioned the blockchain. I keep reading that blockchain is gonna allow us to use smart contracts and have things happen automatically that now have to be manual. What, what’s the problem with blockchain?

[00:54:04] Hilary Allen: Well, first of all, smart contracts can work without a blockchain. Smart contracts predate blockchains, they can run on all kinds of databases. So if, if you want that kind of functionality and it has pros and cons, and I’ve written about this a ton, you can have that without a blockchain. The reason why you don’t wanna have it on a blockchain, and this is something that does not get anywhere near the attention it needs, is that there’s all kinds of operational risks associated with the blockchains themselves. So blockchains are software, they are maintained by, in the case of the Bitcoin blockchain, just a few individuals, in the case of the Ethereum blockchain, it’s the Ethereum Foundation. They’re not regulated at all. They have no obligation to invest in cybersecurity, to invest in getting the blockchains up and running again. Should something go wrong. You’re just, you’re really sort of, as I sometimes say, YOLO-ing operational risk with regards to these, these blockchains. And so if you want smart contract functionality, like don’t use a blockchain.

[00:55:11] Barry Ritholtz: Huh? Coming up we continue our conversation with Professor Hilary Allen discussing her new book, FinTech Dystopia, a summer beach read about Silicon Valley and how it’s ruining things. I’m Barry Ritholtz, you are listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

[00:55:43] Barry Ritholtz: I am Barry Ritholtz. You are listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Hilary Allen. She teaches at the American University, Washington College of Law in Washington DC where she specializes in regulation of financial and technology laws. So we’ve mentioned stablecoin, we’ve mentioned blockchain. Is there any value in any of the crypto coins, be it Bitcoin or Ethereum? I know we, we can’t actually describe the last hundred coins that are out there on the radio. We’ll, we’ll violate George Carlin’s seven words, you can’t say on TV or radio, but there’s a, outside of the, you know, the Doge coins and everything below that, what’s the value of the first five or so cryptocurrencies? Is there anything worthwhile to these or is this just a solution in search of a problem? It’s

[00:56:44] Hilary Allen: A solution in search of a problem. I mean, essentially even, so Bitcoin often is seen as the most credible of these because it’s been around the longest and has the largest,

[00:56:53] Barry Ritholtz: It’s Bitcoin and ETH, that’s, those are the two I hear about the most.

[00:56:57] Hilary Allen: But both of them are essentially Ponzi in the sense that there’s nothing backing them. The only reason they have value is because someone else might buy them from you. If they choose not to, it could go to zero. And actually, someone put it to me this way, it’s not that they could go to zero, they could go to less than zero because they don’t even have any assets that could be used to administer a winding up. Right, right. And, and, and that’s expensive. You know, you, you’re gonna get the lawyers and the courts and everybody involved. That’s,

[00:57:25] Barry Ritholtz: Well you’re not suggesting that if you own Bitcoin you may have a liability down the road. Is that, is that the implication?

[00:57:31] Hilary Allen: No, I’m just saying that if, if someone was trying to work out the end of one of these things, there wouldn’t even be, you know, office furniture you could sell to pay the lawyers.

[00:57:42] Barry Ritholtz: Okay. You, you’ve written about startups like Theranos, I remember Juicero,

[00:57:51] Hilary Allen: Juicero is

[00:57:51] Barry Ritholtz: The best. Tell us a little bit about those two and was that just, you know, one of these products that just didn’t work out? What, what’s the problem with that technology solution to our juicing problems?

[00:58:06] Hilary Allen: So Juicero is just my favorite metaphor for all of this. So for those of you who are unfamiliar with the, the gift that is Juicero, so basically this was a machine that cost hundreds of dollars. It was wifi enabled and well

[00:58:19] Barry Ritholtz: Roll back. The, the guy, and you described this in the book, the guy who invented this previously had set up a fairly successful, was it a juicing chain of companies that got bought. And so he had some credibility in the space and now I’m not gonna run restaurants, I’m going to create a technology that people can juice at home.

[00:58:42] Hilary Allen: And it was venture funded. They put a lot of money into this.

[00:58:45] Barry Ritholtz: A hundred plus million dollars.

[00:58:46] Hilary Allen: And these, these, what it did was it squeezed these juice pouches and the problem was that people could just squeeze the juice pouches with their bare hands and get all the juice.

[00:58:56] Barry Ritholtz: Out. There was, there was a notorious Bloomberg article about this, but why it raises the question, did the company already squeeze the juice and put in these pouches? Why didn’t they, like why wasn’t this set up so that you can actually put fresh fruit? Like doesn’t it defeat the purpose if you’re buying pouches or was the whole idea the razorblade model?

[00:59:22] Hilary Allen: So, I mean, the reason why I love this as a metaphor is it, it really gets at this, this techno solutionism, which is one of the concepts that I’m really coming for in this book. And techno solutionism is this idea that everything in our world can be reduced into a technology problem. And that the only reason we haven’t solved certain things is because we haven’t spent enough time and money on developing the technology. And, and what that does is it, it sort of flattens problems into, it gets rid of the human messiness. It flattens problems, it ignores domain expertise. People who’ve been working in particular fields for a long time and know a lot of non-tech stuff, it, it sort of dismisses their expertise. And sadly, you know, there’s just this magic associated with technology at this point. And, and as I said, I’m not anti-technology.

[01:00:11] Hilary Allen: A lot of it’s great, but it doesn’t deserve the level of sort of magical deference that we give it. It can’t solve all our problems. And when we get into this mindset where we think that if we throw enough money at technology, it can solve anything and it will always be the best solutions. We end up squeezing pouches with a machine that we could squeeze with our bare hands. And, and a joke that I try and make in the book, it’s like, with AI, we may be better off squeezing things with our bare minds.

[01:00:39] Barry Ritholtz: So one more company I have to ask about, Theranos. I love the book Bad Blood. What really went into details about how corrosive and co-opting the company itself was for everybody around it, including the attorneys and, and all sorts of other bad actors. Why wasn’t Theranos just an idea that didn’t work? That you can’t, if you wanna draw blood from a vein, you have to draw blood from a vein. You can’t just prick your fingertip and think that’s gonna be the same as venous draws.

[01:01:16] Hilary Allen: Well, so that’s the thing with this techno solutionism, it presumes that everything is a tech problem waiting to be solved. It doesn’t even countenance the possibility that there may not be a technological solution for what you wanna do. That the technology you want may not be able to do the thing you want it to do. And when you have that sort of collective sense that I think we have now that if we throw enough money at any technology, it can solve any problem we give it. You can see how people get so susceptible to being sort of drawn in the stories that outright con people like Elizabeth Holmes might be telling, but also the stories that were being told about, you know, about AI right now and about crypto. You know, the more you know about these technologies, the less impressive they seem and the more clearly it becomes illuminated that, that they just can’t do a lot of the things that they’re going to do. But that’s so counter to how we typically talk about technologies that it sort of, it feels a bit weird to talk like that and, and you sort of, you’re going against societal norms in a way. And so one of the things that I really wanted to do with this is to start making it easier to talk about these things critically to be not such an outlier to express your frustrations. And I think we’re actually having a moment like that about AI. ‘Cause so many people really hate it. Hmm.

[01:02:45] Barry Ritholtz: Really? So, so you use the phrase techno solutionism and Theranos is really the poster child for that. ‘Cause as you’re describing a lot of these things, I am recalling the story. Especially what you’re referring to with domain expertise. She had no medical or medical device training. None of the VCs who put money into Theranos were healthcare, biotech, medical devices. Like they all passed. Eventually she hired a number of people to try and with some background, but they seemed to turn over pretty quickly because no, you can’t do that. What, you just pricking the skin, you’re getting all the interstitial tissue and fluids and you’re corrupting the sample that you want to test for something. You have the, the reason we draw from the vein is very medically specific and yet it attracted Henry Kissinger and all sorts of big law firms and everybody plowed in. She’s the next Steve Jobs, the youngest self-made female billionaire. What is it about us that we’re just so susceptible to buying into these narrative tales that turn out to be nonsense?

[01:04:08] Hilary Allen: So I mean, part of it is that we’re humans and humans have often sort of been snowed by things that are flashy and shiny and exciting. I mean, that, that’s just very much the human condition. Some of the stuff I talk about in the, in the book that I really enjoyed working on was the cognitive psychology aspects of it. You know, sort of when we hear certain stories, it’s very difficult to budge ourselves and, and be contrarian. And I was, as I was saying earlier, so you sort of need a, a collective tipping point where people start to question it. So you don’t feel like an outlier or the norm when you start to question these things. And so I think there’s a role for media here. I think there’s a role for education. Unfortunately, the people who benefit from techno solutionism also know this and have a very big media presence and invest a lot in education. So it’s, it’s an uphill battle to start talking about these things differently. But, you know, ultimately we, we are all human and it’s nicer to believe that something will succeed than that it will fail. I mean, you might not think I’d be much fun at cocktail parties, although I am.

[01:05:24] Barry Ritholtz: And the book is available for free at fintechdystopia.com. Let’s jump to our final questions, our favorite questions we ask all of our guests. Starting with tell us about your mentors who helped steer your career.

[01:05:42] Hilary Allen: So my first mentor is probably my first law firm partner boss in, in Australia, Stephen Kavanaugh. And I had thought I was going to be an IP lawyer, but we had a rotation system and I ended up in his financial services practice. And he was just a wonderful person to work for. It was a time when the law had just changed in Australia and, and he really was willing to hear what I had to say about this, this new law. And so it was just, I just felt very invested in and that was lovely. And then I think as an academic, Patricia McCoy, who I adore sort of, I have had a very non-traditional path to academia. I had more practice experience than is usually the case. I had fewer of the bells and whistles credentials that people usually have. And again, she just saw in me someone who was really passionate about preventing financial crises, about sort of systemic risk and, and sort of was willing to look through the fact that I wasn’t as polished as most of the other people trying to enter academia and support me. And I was very grateful for that.

[01:06:54] Barry Ritholtz: We’ve talked about a run of different books. What are some of your favorites? What are you reading right now?

[01:07:01] Hilary Allen: Oh, I was an English lit major. So I’ve, I have many favorites. I’m, I’m very into the dystopian tracks. So Handmaid’s Tale, surprise, 1984. Yeah, surprise. I just finished The Parable of the Sower in that vein, which was

[01:07:13] Barry Ritholtz: Parable of the,

[01:07:14] Hilary Allen: The Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler. I also have always had a soft spot for really good children’s literature. So Philip Pullman’s Dark Materials trilogy is one of my favorites. And and right now I’m reading with my kids Catherine Rundell’s books Impossible Creatures and The Poison King. And it’s just, they’re just so good. And then work-wise, I’ve just started Jacob Silverman’s Gilded Rage, which is very much on point for the conversation we’re having.

[01:07:45] Barry Ritholtz: Gilded Rage, you know, we talked about a few crypto related books. Did you see Zeke Faux’s

[01:07:52] Hilary Allen: Of course, Number Go Up.

[01:07:53] Barry Ritholtz: It, it, it really is just an astonishing, astonishing work. What sort of advice would you give to a recent college grad interested in a career in whether it was law, financial technology, regulation? What’s your advice to those people?

[01:08:11] Hilary Allen: It’s a really hard time for them, and I, I talk to my students a lot about the careers and, you know, things are, the ground is shifting under our feet and in this time of uncertainty, it’s really, it’s really hard to figure out what to do. So I would recommend investing in the fundamentals. And I think it’s, it’s hard to do when AI is being pushed, but, but becoming a good communicator, learning how to write and speak to people clearly, will never, I think, go outta fashion. And investing in relationships, again, we’re in this time where everything is sort of becoming technologized and atomized, et cetera. But in my career, having good relationships with people, and I’m pretty sure you’ll agree with this, has been one of the most successful things that has helped me along the way. And so just investing in personal relationships, I think is, is always good advice.

[01:08:59] Barry Ritholtz: And our final question, what do you know about the world of FinTech investing regulation today that might have been useful 20, 25 years ago?

[01:09:11] Hilary Allen: Well, honestly, I’m not sure that there’s much, because the world was very different 20, 25 years ago. You know, I, I always just invested in, in index funds basically. And, and, you know, and, and that worked out frankly, great for me.

[01:09:27] Barry Ritholtz: Worked

[01:09:28] Hilary Allen: Out really well. The challenge is, and I study financial crises, the challenge is that when things go horribly wrong, everything is correlated. Everything is correlated.

[01:09:39] Barry Ritholtz: All correlations go to one in a crisis for sure.

[01:09:41] Hilary Allen: And I think we’re on the brink of a crisis.

[01:09:45] Barry Ritholtz: When you say on the brink, days, weeks, months, years.

[01:09:49] Hilary Allen: Ah, well, John Maynard Keynes said that the markets can stay irrational longer than you and I can stay solvent. So I will never put a timeframe on it, but I, you know, all warning indicators are flashing red at the same time as we are pulling back all regulatory apparatus. So I think it’s safe to say we are on the brink of a crisis. How,

[01:10:06] Barry Ritholtz: How could that ever go wrong?

[01:10:09] Hilary Allen: How could it go

[01:10:09] Barry Ritholtz: Wrong? Just regulation leeches the animal spirits. As long as we’re talking about Keynes, it’s all good.

[01:10:18] Hilary Allen: Perhaps not.

[01:10:19] Barry Ritholtz: Perhaps not. Hilary, thank you so much for being so generous with your time. We have been speaking with Hilary Allen, professor of law at American University, Washington College in DC, an author of the book available for free online, FinTech Dystopia, A Summer Beach Read About How Silicon Valley Is Ruining Things. If you enjoy this conversation, well check out any of the 600 previous discussions we’ve had over the past 12 years. You could find those at iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, Bloomberg, or wherever you find your favorite podcast. I would be remiss if I didn’t thank our crack staff that helps put these conversations together each week. Alexis Noriega is my video producer. Sean Russo is my researcher. Anna Luke is my podcast producer.

I’m Barry Ritholtz. You’ve been listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

~~~

The post Transcript: Hilary Allen on Fintech Dystopia appeared first on The Big Picture.

Recent comments